What I've Been Reading

Didion's Democracy, extreme soccer violence, The Rock, a puppet convention

Of all her celebrated writings, Joan Didion was most proud of her novel Democracy, which received mixed reviews when it was published in 1984. I found it very sly, very clever. At first it seemed as if it might be too clever, but then the characters snapped into focus and I was all in.

At the center lies Jack and Inez. Jack must be named Jack because he’s CIA. Like a journalist, Jack deals in information. But the information Jack holds does not end up on the front page. In fact, that information should never produce a story because the black and white of newsprint could not possibly capture the grey matter he deals in—non-state actors, international waters, and where to refuel aircraft carriers over the Pacific. Jack’s information should never grace A1, but that is precisely where this story begins and ends: a front-page investigation into war profiteering.

Inez is Jackie Kennedy Onassis recast in an alternate universe where there is no fabled Camelot, no blood-soaked pink Chanel suit, no grassy knoll in Dallas. In this universe, which is more of an island, an island host to the highest echelons of society—CEOs, models, ambassadors—it is already understood that America is not exceptional and in decline. On this island, there is no room for delusional thinking and no room for privacy either. Life is lived in the public eye and told through Didion’s discerning eye.

Democracy is a work of New Journalism despite being fiction. In this lithe novel, Didion applies her talents as a reporter and does what she does best: dispatches with surgical skill, reveals with astute details, and then extinguishes her barely smoked cigarette and leaves the room.

Bill Buford’s violently entertaining book Among the Thugs will make you fond of saying lads. You might even find yourself equal parts fond and appalled by the lads Buford, an American journalist and soccer novice living abroad in Cambridge, befriends as he seeks to understand the widespread violence routinely incurred by soccer hooligans in 1980s England. You will certainly chuckle over Buford’s descriptions of these hooligans, which alternate between catty and deadpan, as well as his steady drip of self-deprecating humor. But mostly you will furrow your brow in shock and disbelief at the volume, degree, and casual nature of the violence committed by this unruly crowd.

Knifings, fractured skulls, kicked-in teeth, and slashed tires are so commonplace on football Saturdays that they rarely warrant news coverage. These weekly exorcisms are wince-worthy, to be sure, but there are also violent acts so creative and so original they could only be described as inspired. These instances will take your breath away and on its way out, it will say, “What the fuck.”

Take Harry, for example: “Harry wrestled one of the policemen to the ground, lifted him up by the chest and then head-butted him—inflicting a hairline crack across the forehead. With the blow, the policeman must have lost consciousness if only because he seemed to offer so little resistance to what Harry did next: he grabbed the policeman by the ears, lifted his head up to his own face and sucked on one of the policeman’s eyes, lifting it out of the socket until he felt it pop behind his teeth. Then he bit it off.”

As I said, they’re an ugly crowd, these lads. But the grotesque is often more fascinating than the beautiful, and so it is with the Man United “firm”—a weekend crew who roam the streets of England waiting for something to happen. The sound of glass shattering is usually the trigger, signaling to the throng of supporters that a threshold has been crossed and that the violence can now begin.

This is what Buford ultimately seeks to understand—how crowd violence lightnings into existence, unleashing a mob of pale, overweight lads hellbent on seizing a city that is already theirs. His sociological study of the mob successfully anatomizes a crowd’s behavior, breaking it down into a series of stages which are advanced by transgressing various norms and laws. First, the supporters congeal into a crowd, making themselves into a single organism high off its own potential power. The second threshold is the destruction of property (the aforementioned glass shattering). The third threshold is violence to flesh. The final stage is complete lawlessness.

The second half of his project—understanding the psyche of the mob—falls short. His working hypothesis, that these violent football supporters are also members of the disenfranchised white working class, quickly unravels. Almost all are gainfully employed, some are even their own bosses. Which makes sense if you think about it. A certain cash flow is necessary to attend a match every week, which sometimes requires travel, and always requires many, many pints.

To his credit, Buford doesn’t bludgeon his working hypothesis. He respects the facts and becomes genuinely confused over why any of this occurs. But he sticks with the lads, joining them in the pub, the pen during the match, and into the streets after as they all wait for something to happen. After a few of these happenings, a new feeling emerges from the fog of confusion and that feeling is an intoxicating high that accompanies transgression and that is doubled by getting away with it. It is the high that accompanies unchecked power.

I recommend starting this book with a pint, as I did, though I warn you will probably order another and then another as you try to keep up with Buford and the lads.

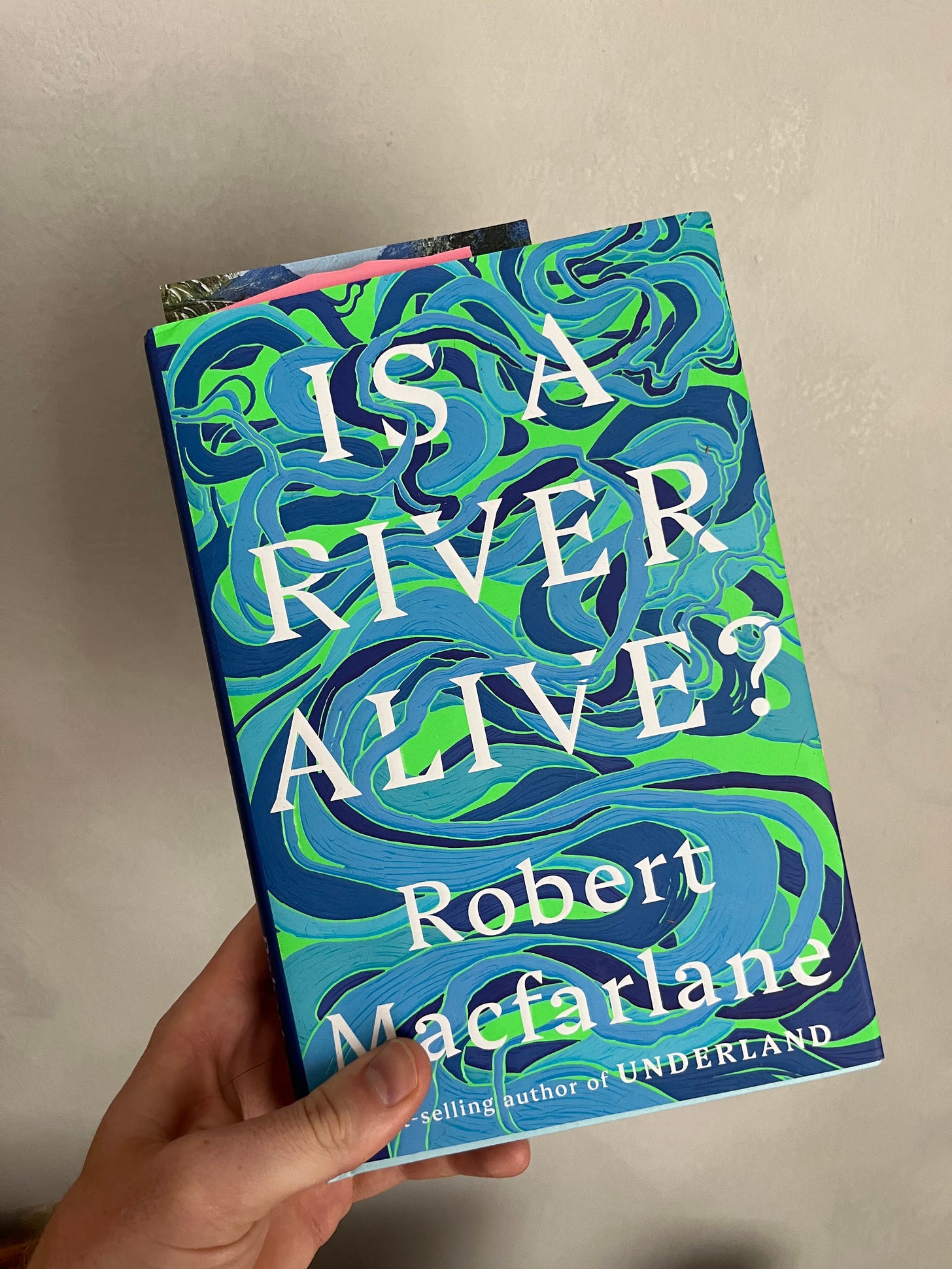

Robert Macfarlane is one of the loveliest writers working today. His descriptive powers are unmatched, particularly when it comes to nature. His book Underland is one of my all-time favorite books. (I don’t remember who I lent my copy to, but if it’s you—give it back!) Like John McPhee, Macfarlane has the uncanny ability to make geology come alive in a theater of seismic action unfolding at unseen depths and over many millenia.

His latest book asks and is titled: Is A River Alive? This sounds like a metaphysical question, and it is, but Macfarlane approaches it from a legal angle. This is not without precedent. In a landmark decision, Ecuador’s Constitution was rewritten to recognize that a river was entitled to certain rights. The right to run free, persist, and regenerate. This decision came after decades of rampant mining discolored the river and poisoned its waters.

Macfarlane visits the cloud forest of Ecuador to see these protected rivers for himself. He also visits a terribly polluted river in India wounded by 24-hour chemical plants and wild rivers of Canada imperiled by dams.

I only made it to India before I put this down. I prefer Macfarlane’s studied observations of the elements over his on-the-ground reporting in far-flung locales. One gets the sense that these reporting trips unfolded over the course of a few jet lagged days and were reconstructed from hurried notes. In the human realm, his purple prose appears all too precious. His elemental stuff—nature observations, etc.—are the product of many moons, carefully considered and reconsidered, and their Edenic character feels apt to his cause.

In addition, here’s a few online pieces I’ve enjoyed lately:

Sam Anderson’s new profile of The Rock in NYT Magazine. I don’t care much for celebrity profiles but I do respect the challenge it poses for a writer: to say something interesting about someone who lives in the public eye and has already been subjected to countless profiles/interviews and to accomplish that when you only have an afternoon with the subject. (“Scheduling an interview with The Rock feels like trying to set up a coffee date with the king of England.”) Anderson flexes his descriptive powers to embody a man who is largely famous for his body, describing his smile as a “shining white charisma-bomb” and his torso as a “sentient pile of cantaloupes.”

I subscribe to way too many newsletters but without fail I open Longreads every Friday. They curate lists of longform journalism and on my commute I read a few from this maps-based list. I recommend Daegan Miller’s story on Thoreau surveying the Concord River.

Mina Tavloki. Remember the name and click when you see it. She is very funny and always writes a killer lede. I recommend starting with Planet Puppet, recounting a weekend at a ventriloquism convention in Kentucky. Her most recent piece is a dispatch from the Westminster dog show and is the first installment in a new “hyperoccassional” column of reportage n+1.

And here’s some river photos I found in my phone.