Shaker Mania

On celibacy, American design, and the theatrical flop of “The Testament of Ann Lee”

After wolfing down some kung pao tofu, C and I went to a New Year’s Day screening of The Testament of Ann Lee at Village East, which houses a cathedral-like theater where operas or vaudeville acts must have once taken place. All I knew about Ann Lee was that it was about the Shakers, and all I knew about the Shakers was that design carried spiritual meaning and I only knew that because our friend Sav lived near New Lebanon, which was once headquarters for the utopian Christian offshoot whose following topped out around 6,000.

I was keen to learn more about the Shakers, but about a quarter of the way through the movie, amid a minutes-long close-up on a singing Amanda Seyfried that had me wondering: how did I get here? I leaned over to C and whispered, “This might be terrible.” This realization hit me as Ann Lee was having her own epiphanies. After being jailed for disrupting a mainstream sermon, Ann Lee has a vision that would come to define the Shaker belief system and elevate her from impassioned believer to the group’s most influential leader and, in the eyes of her most devoted, the second coming of Christ.

In Ann’s vision, which was accompanied by a song that repeated “I hunger and thirst” ad nauseam (did I mention this was a musical?), an oily snake glides across the screen, flicking its tongue like a lit cigarette. The juice of a bitten apple courses from lip to chin. A naked man and a naked woman coil around one another. What Ann sees is original sin. What we see is more sex. Up until this moment in the movie, the prevailing tone has been erotic—the sun lancing through a white night gown to reveal a morning buttocks, that same buttocks being slapped with a bristly hand brush and met with rousing moans as her husband Abraham reads scripture aloud. But after four unsuccessful births, a despondent, incarcerated Ann becomes convinced that the reason for her maternal misfortune and all human misery lies in sex. Fornication, she tells her fellow Shakers, is the cause for wo/man’s estrangement from God. Only through celibacy does one stand a chance of growing closer to Him. Some, like Abraham, furrow their brow at this revelation, but most adopt it immediately and without complaint like her brother John.

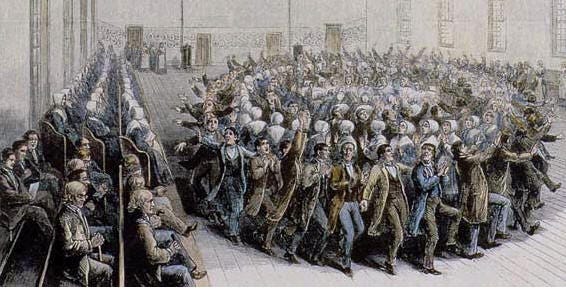

But the erotics did not stop there. It was merely transmuted into the Shaker form of prayer, which took on an intensely physical quality and placed new importance on breathwork. Shaker praying was modern-day raving. Everyone danced madly, alone but tapping into something communal and deeply felt: a common cause, a dissolution of self, an absolvement of wrongdoing.

I took many issues with this movie, but the choreography was not one. The director Mona Fastvold’s ham-fistedness tarnished most of the movie, but when redirected at the body this fist produced a seductive, somatic cadence that had everyone tapping their feet, keeping time with flesh and heartbeat.

The Testament of Ann Lee suffered most from the lack of any compelling storyline. Instead what we were given was a 2h 10m music video laced with epic shots, a few decent songs, excellent choreography, and absolutely zero narrative thrust. The script was so badly butchered that the only thing that moved the plot forward was a much-abused voiceover. I kid not, 40% of the movie was voiceover, another 40% was song, 10% was breathing and the remainder was acting. Unless you’re making a documentary, that amount of voiceover is inexcusable. It made for a herky jerky viewing experience wherein acting did little to advance the narrative, song interrupted what little progression was being made, and then voiceover leapfrogged us forward.

The conspicuous absence of a plot made for a wristwatch-checking movie experience. Conflict sometimes knifed through, but usually we were only allowed to see its tidied up aftermath. Indeed, I could count on one hand the number of times any character’s face had the look of something other than adoring adulation. Our principal character, Ann, had no development arc. Saintly and strong-headed from her earliest days, she remained so for the rest of her days. Whatever hiccups might appear on the road, were easily papered over, usually by a convenient voiceover.

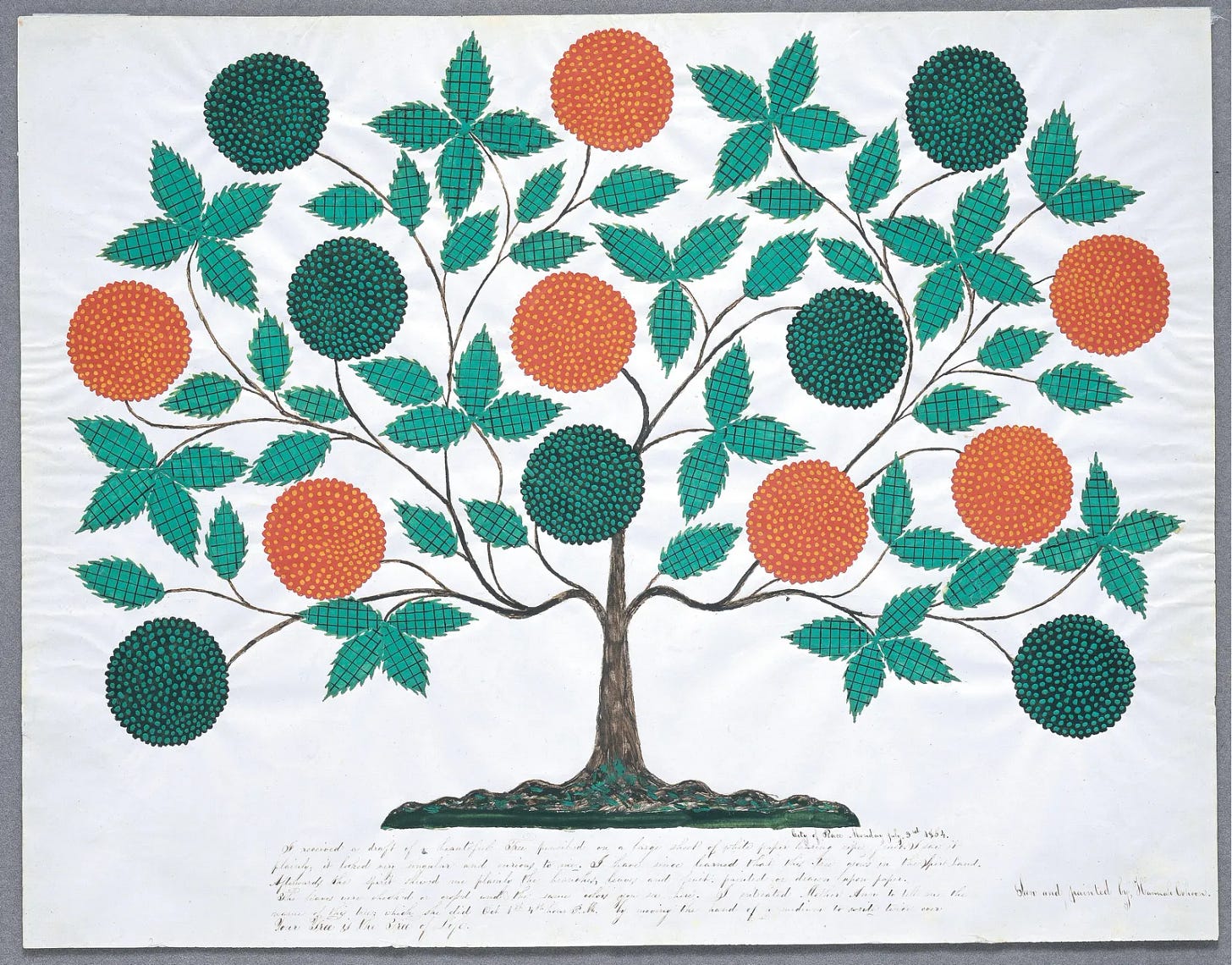

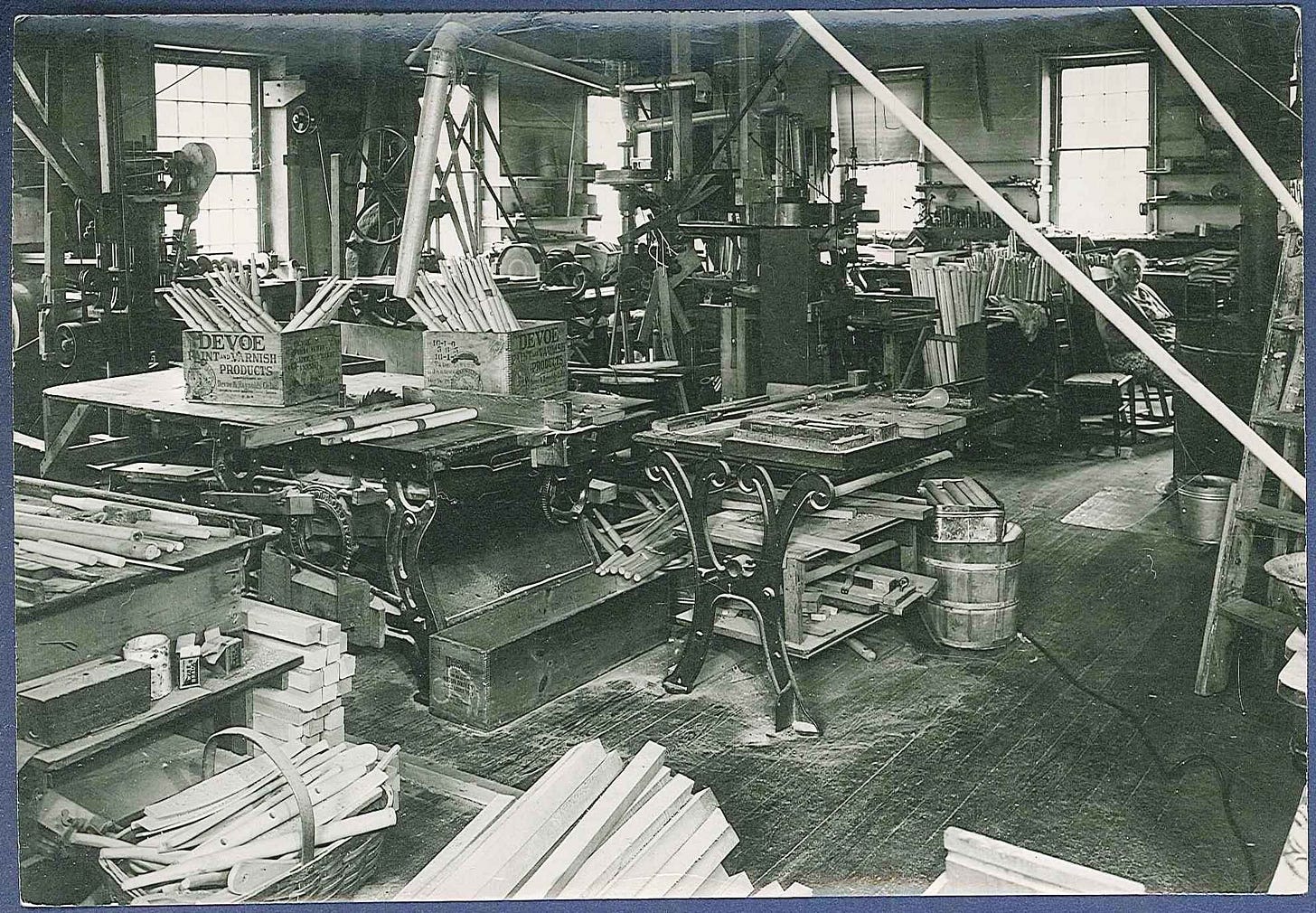

For a movie that catered to so many modern sensibilities, I’m shocked they didn’t leverage the Shaker’s renowned craftsmanship. They were artisans and woodworkers of the highest order who believed that form should follow function. The result was simple furniture made elegant through complex joinery that masked any visible use of nails. Ladder-backed chairs and twin bed frames were enjoined using dovetails, mortise-and-tenons, and pegs. Pegs, in particular, were a Shaker signature. Most rooms came lined with a long, chest-high peg rail where any item not in use was meant to be hung. Chairs were a bestseller and were eventually trademarked by their Mount Lebanon factory, which had become an epicenter for Shaker artisans and industry.

Shaker furniture and its influence on American design is arguably where the Shaker legacy lies. Devotion to God was exercised in work ethic. The relentless pursuit of perfection was a means of measuring proximity to God. In short, work, like dance, was a form of prayer.

But instead of giving any airtime to craftsmanship, Fastvold chose to focus on the Shaker’s doomed evangelizing efforts. The spread of Shakerism was never in question. Their vow to celibacy precluded any meaningful proliferation. As of 2024, there were only two Shakers living in a small village in Maine 30 minutes north of Portland. This is their Adam and Eve.

But despite their paper-thin ranks, Shakers are having a moment. A museum devoted to Shaker history and culture is set to open in Chatham, New York. The Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia will be opening an exhibition later this month about Shaker craftsmanship, using items on loan from the museum. And last year, the number of Shakers jumped from two to three.

The observation that Shaker prayer was essentially modern-day raving is spot on, the communal dissolution of self through physical movement rather than verbal expression. What I find interesting is the contradiction you mention where the movie stripped away the craftsmanship angle even though work was literaly a form of prayer for them. The choreography translating their breathwork into something visceral probably carried more of their actual spiritual experience than all the voiceover exposition combined.

You definitely found another calling as an excellent movie critic. Based on your description, it sounds like I would've been a very happy participant in the shaker prayer/rave.