Reframing My Father

How unseen family photos revived my anxieties and unraveled the story I’d been telling myself.

It is getting harder and harder to picture my father. When I do manage to summon his image, it belongs to a photograph. I did not take many photos of my father — he was not exactly photogenic, especially later in life. He wasn’t mindful of such things — appearances, documenting lives — but I was.

Back then, it was a relief to look away. No doubt because his disheveled appearance was evidence of a life unraveled. I saw his obliviousness in the embankments of dandruff gathered around his shoulders. I saw in his greasy brown hair his inability to care for himself. I felt his humiliation, and mine, in the gap where his front tooth fell out from neglect. I also saw in his watery eye, the one that didn’t work, unwavering attention. When our eyes met, I felt his devotion: to the moment, to me, to whatever it was we were sharing then and there.

It pained me to look at my father then, and I dreaded introducing him to the world and my people in it. But now, as I approach the one-year anniversary of his death, what pains me is the fact that I have so few photos of him to look at.

So much had been taken away so quickly in my Dad’s final year. He lost his ability to walk and live independently, forcing him into an assisted living facility. With seemingly no other options, I got rid of nearly all of his belongings, including his vast book collection. And then I lost him.

I remember desperately scrolling through my phone looking for pictures of my Dad on the flight home to say my final goodbye. Of the tens of thousands of photos in my camera roll, only a few dozen included him.

I understood the loss was irrecoverable when I woke up the next morning and remembered it all again through tears. The previous night had been so surreal: feeling hungry as my Dad lay dying, laughing when he gasped back to life, not crying when I should be weeping, saying the same stupid words over and over hoping they might mean something or, at the very least, reach some part of him so he knew he wasn’t alone at this final hour. Recounting that night the following morning was like a second death. I grieved the fact that he was gone forever, and then I grieved the fact that I had so little to remember him by.

In the week after his passing, I documented as much as I could. Everything felt precious, if not prescient, as I raced to record my every thought and emotion. An urgency unlike any other graced my diary as I filled page after page. I’d never had so much to say, and it felt good to say it, if only silently and privately. With so few photographs and only a sliver of his book collection, I was desperate to preserve all I could, even at this late hour.

And then I lost that notebook just a couple of weeks later. Yet another irrecoverable loss. It was that kind of year for me.

Now, in the weeks leading up to April Fool’s Day, I reach for what I do have of him: a half-full album of photos and letters of correspondence, poems he wrote/emailed me, a shelf of books, and everything I’ve written about him in the past year.

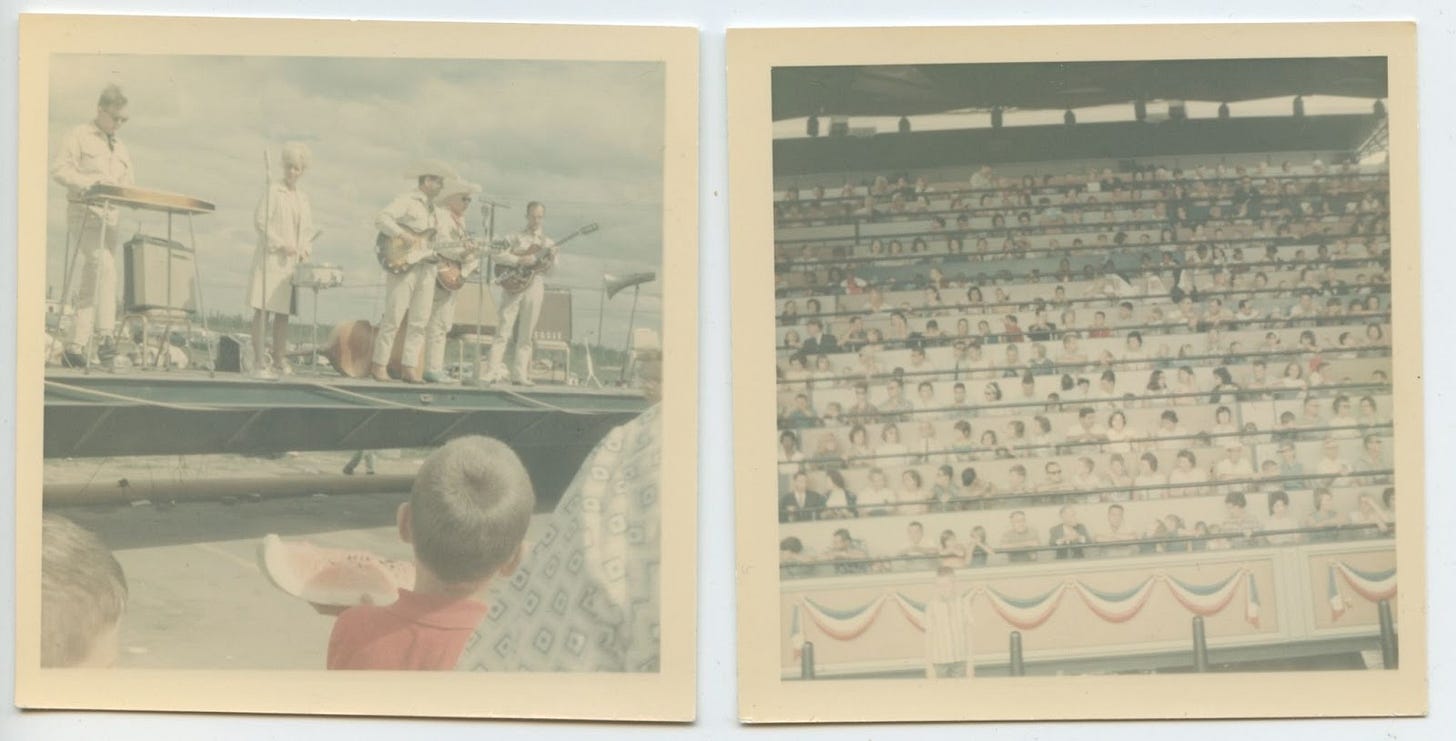

I’ve been looking at the photographs more and more, especially an early set from my Dad’s childhood that I discovered while clearing out his apartment. They smack of Americana, and that nostalgia is what initially drew me to them. Some don’t even feature my Dad, but they all depict a slice of American life that now appears as a quaint relic of the past.

But when I stopped treating them as Americana and started viewing them for what they were — family photos — they took on a darker character. Moving past the vintage veneer, it was suddenly eerie how distant, small, and alone my Dad appeared in them. He was often photographed from such a distance that he blurs into anonymity. If I hadn’t found these among my Dad’s belongings, I don’t think I would have recognized my father in this stiff, squinting child.

The child with the buzzed head looks like he didn’t want to be there. He wears the same miserable look whether he was at the county fair, at his communion, or at home. This kid looked like he might hurt you, might throw stones at mail boxes, moving cars, and trilling birds. But knowing what I know of my father, he was the one hurting. The steely gaze of this child, who could not be a day over ten, is alien to me. The father I knew had the constitution of a gummy bear — soft, squishy, overly sweet — and cried at the drop of a hat.

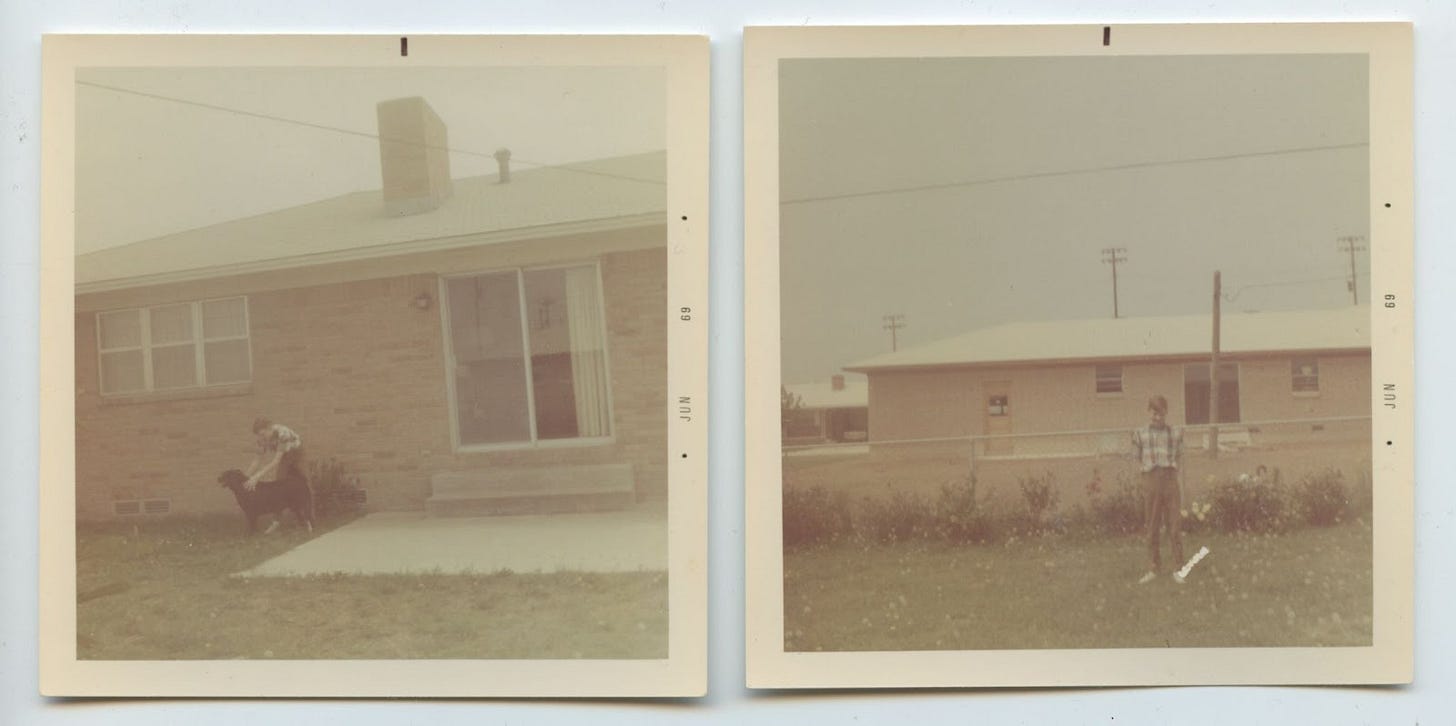

I began to recognize my father in a series of photos taken outside a single-story brick house. I’ve been to this house, long ago, after my father’s father died. I was fourteen when my Dad and I drove down to Claremore, Oklahoma to clear the house of junk and ready it for sale. For five days, we tossed bushels of stuff into an industrial-sized bin my Dad rented that was too tall for me to see over. It was a hoarder house so we had to work efficiently. In every room, there were knee-high piles of magazines and that is all I can remember throwing away. Occasionally, I’d climb the few rungs on the side of the bin to peer inside at the universe of things that make up a life, marveling at the speed and indifference with which a person’s belongings can be dispatched.

The collection of photographs I am holding were originally recovered from that house. My father kept them, along with other family archival documents — letters of correspondence, news clippings, memorial books — that I rediscovered sixteen years later clearing out his apartment, once again marveling at the speed and indifference with which a person’s universe can be bagged, binned, and never seen again.

While studying these photos one wintry evening, my father appeared as a ghostly apparition. I was puzzling over how to structure this essay, looking back and forth between the snow parachuting down outside my window and my desk where I had grouped polaroids into sets of four. In the “Americana” set, I noticed a slight aberration in the foreground of a photo of a ribboned grandstand. Holding it up to the light I could see the vaguest outline of a figure in a striped shirt. I cross-referenced it with the others and saw my Dad in a striped polo in another photo posed next to a donkey and a clown. These two pictures were likely taken the same day, perhaps at some county fair.

The pose was also familiar. In nearly all the photos from this era, my father appears at once rigid and deflated. His arms hang limply at his side, unsure what to do, while his posture is vaguely militant in its constriction and lack of expression.

In this grandstand photo, my father looks more like an absence than a presence. He disappears almost entirely into the crowded scene behind him. I’m sure there’s a technical explanation for the effect — overexposure to the sun at the moment of capture, the rub of time gently fading color — but it struck me as an erasure at first glance.

Upon reflection though, I’m not so sure. I don’t believe in ghosts, never have, and I don’t believe in angels, try as I might. But when his figure finally appeared before me in the photo that snowy night, it felt almost like a visitation. I witnessed my Dad as a light-filled being, not smeared out of existence, but shining his way through. I imagined him as a lighthouse, tending the flame for all who dare to look.

It was upsetting to look at these photos for as long as I did. I can no longer tell if I’ve brought misplaced baggage to my interpretation, or if the photos have simply revealed their true nature following close examination, because what I see is an unhappy child.

I see a child who looks ill at ease, even humiliated at times. Was photographing my Dad next to a donkey and a clown a joke? And for whom? Because it seems cruel by association and by judging the look on his face. My Dad isn’t laughing, and I’m fighting tears. In fact, he isn’t smiling in a single photograph from this era. He was always a little camera shy, much the way me and my brother are, but his appearance in these photos stood in marked contrast to photos of my Dad later in life. Knowing what I know, I suspect it had something to do with the man behind the camera: his father, my Grandpa John.

It was Grandpa John’s neglect — not the sun, not time — that smeared my father out of existence. It was he who framed my Dad, capturing him from a cool distance, rendering him faceless, shrinking him into the world.

I did not know my Grandpa John well, save for a handful of facts and visits. I know that he was from Iowa, that he had at least three wives, and that he worked as a mechanic in the Air Force and later for American Airlines. It was thanks to this last fact that we were able to fly for free on standby back East to visit my Mom’s family and out West to visit him in San Diego. I also know he and my Dad were never close.

My Dad grew up as an army brat, moving with him from one base to another whenever duty called. Uprooting every few years made it difficult to make friends and my Dad never mentioned any friendships that predated his college years. By the time he graduated high school, he had lived in five different towns.

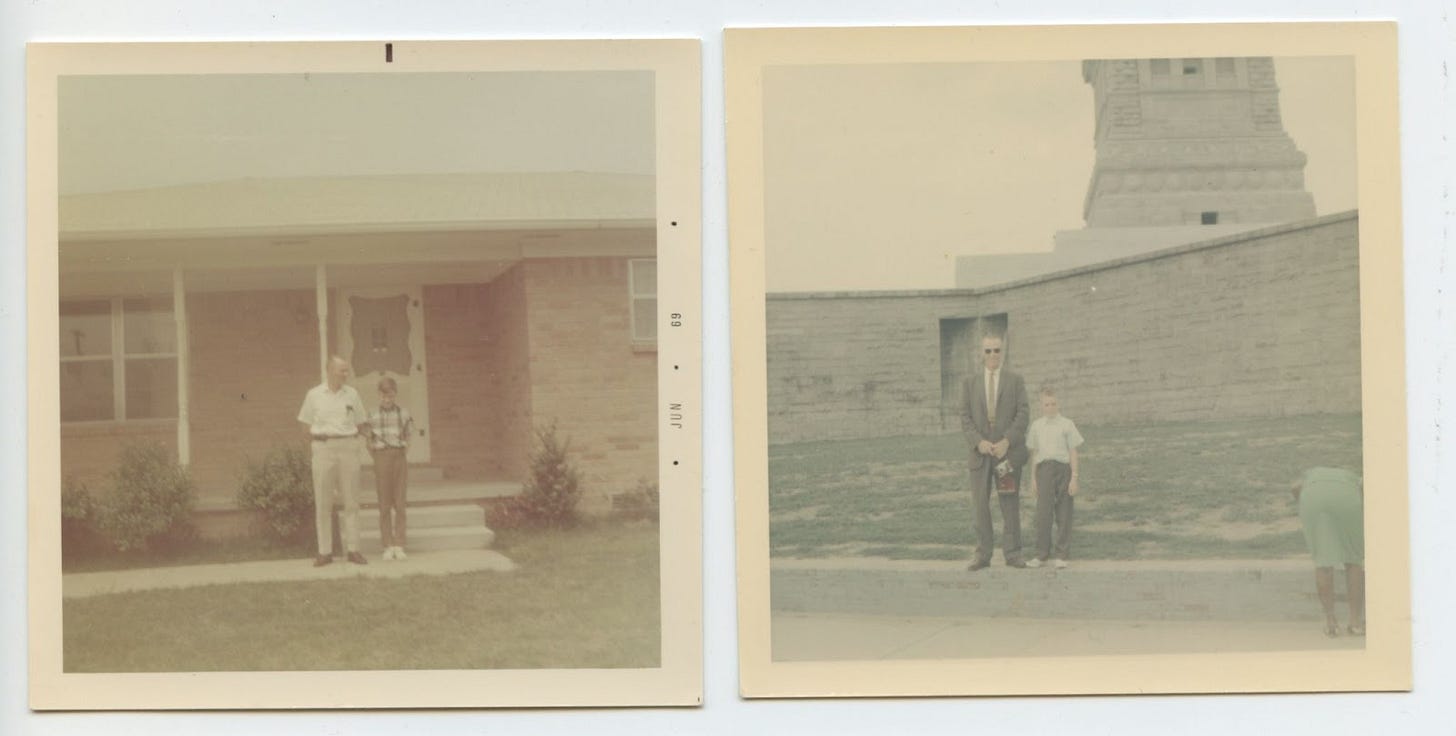

His nomadic childhood was made more lonely by the fact that he was an only child being raised by a single father who didn’t know how to love his son. The icy nature of their relationship is evidenced by the only two photos of them together. They stand stiffly side by side like two magnets with the same charge, disallowing them from ever actually touching.

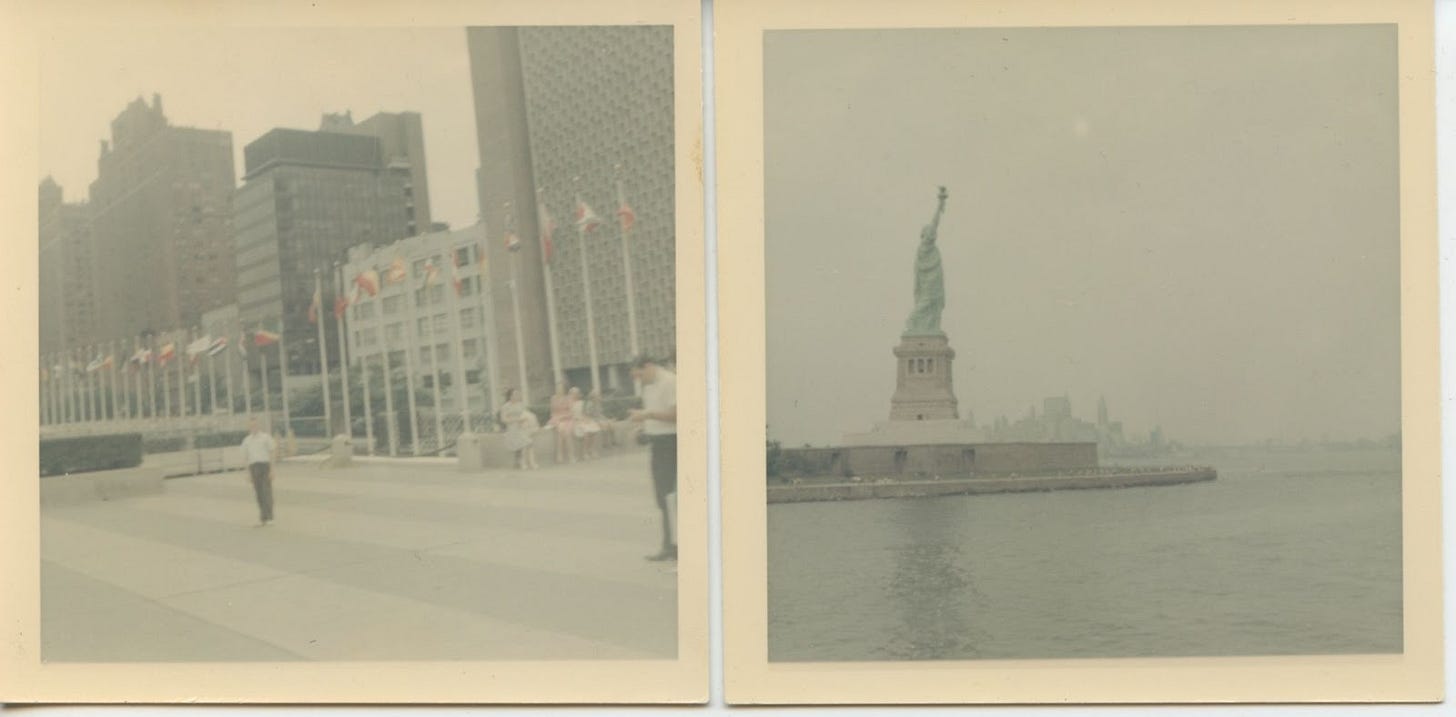

My Dad visited New York twice in his lifetime: once with his father to sightsee, and once as a father to see me. The little documentation I have of that first trip shows the United Nations building and the Statue of Liberty. They appear together in a photo taken on Ellis Island with a truncated Statue of Liberty rising in the background. Grandpa John is dressed smartly in a suit and shades, smiling while holding a camera. My father, who must’ve been eight or nine, is wearing loose brown slacks and a tucked in polo shirt buttoned to the top. (My father rarely dressed this nice as an adult).

The other photo is dated to June 1969 and was taken in front of their ranch-style house in Oklahoma. My Dad would’ve been thirteen and about to matriculate into high school. Here they are centered in the frame, each with their hands formally clasped behind their back. My Dad’s head nods slightly forward but his gaze lifts to meet the mechanical eye. Grandpa John appears distracted, as if a sudden sound — a dog barking or a car honking — seized his attention at the moment of capture. This portrait, with its jaundiced fade, rigid formality, and front porch setting, calls to mind the photo used in Succession’s opening credits. It’s not clear to me who took either of these photos.

While these are technically family portraits, there is no detectable warmth. I sense instead an open chasm, one that is deepened by my conviction that there should be loving warmth between father and son.

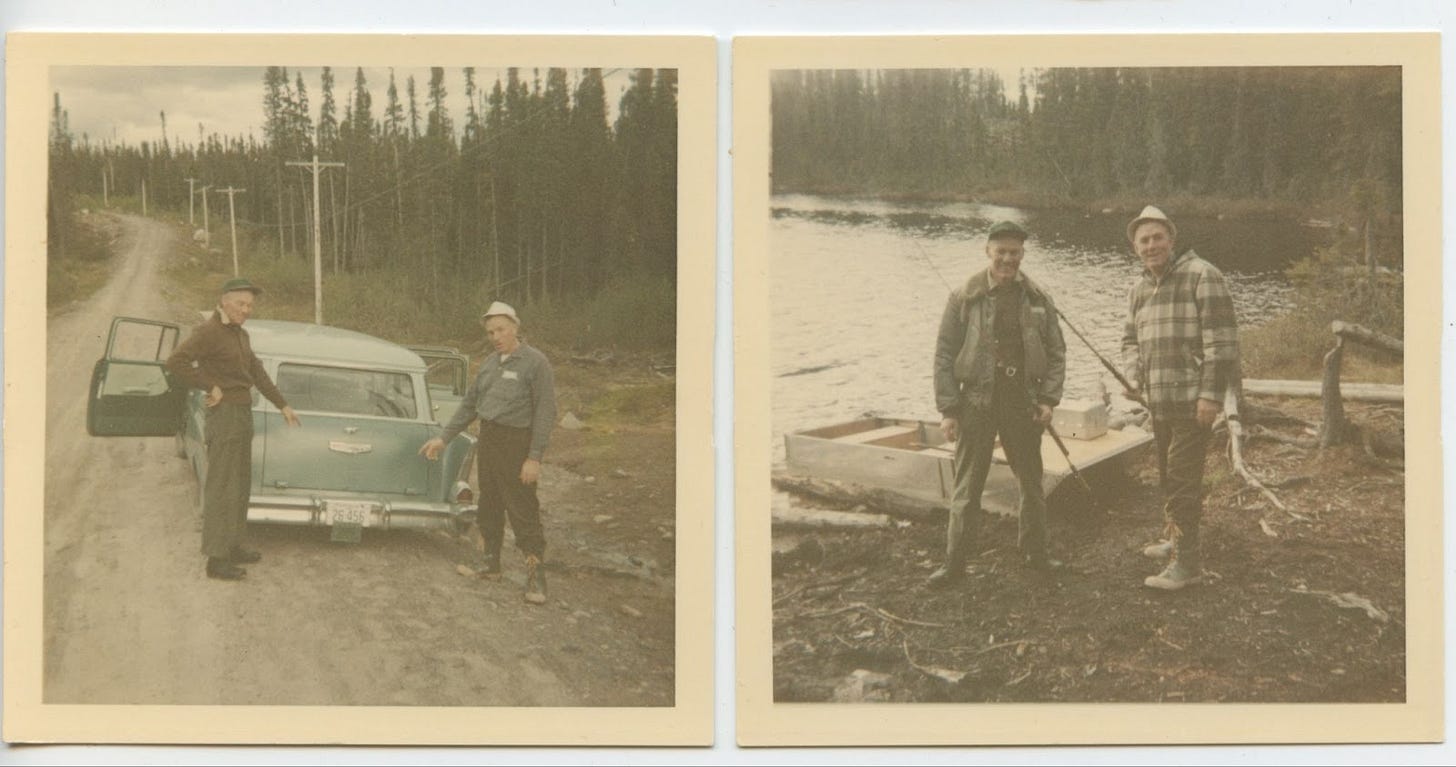

The mood of these square prints totally changes in photos showing Grandpa John and Uncle Ray. The mood is relaxed, playful even — grown men grinning like boys, as if they winked their way out of trouble. They’re seen fishing, mounted on bikes, hauling Canadian Club whiskey, and pulled over on a dirt road cutting through the woods. These are reminiscent of photos my friends and I took in highschool. A portrait of Cale’s car, which took us all over the country on a month-long road trip after graduating, not to mention countless photos of us biking all around our hometown until the sun went down and then some.

What none of these photographs show is an image that haunts me.

I had never seen a picture of Grandma Phyllis before my Dad died, but I always imagined her with freckled shoulders and soaped toes because I’d never pictured her anywhere but in the bathtub that would become her grave.

Home alone with her baby boy, Phyllis drew herself a bath and, once submerged, her epilepsy triggered a seizure. I imagine her clenched throat exposing itself to the heavens as the back of her head digs between her shoulder blades. I imagine thrashing limbs sending bathwater storming over the tiled floor. I picture my Dad, just two at the time and seated beside her, upset and crying but unaware of what’s happening. The most chilling part of this scene is how everything — her baby boy, the edge of the tub, the air above the liquid surface — was all within reach. And yet.

I wonder how long my Dad was alone with his dead mother. I wonder who Grandpa John reached for first when he returned home: his dead wife or his baby boy?

I wonder if either of the Goodwins understood how this tragedy effectively orphaned my father. This is not technically true, but I believe it is true enough considering what ensued.

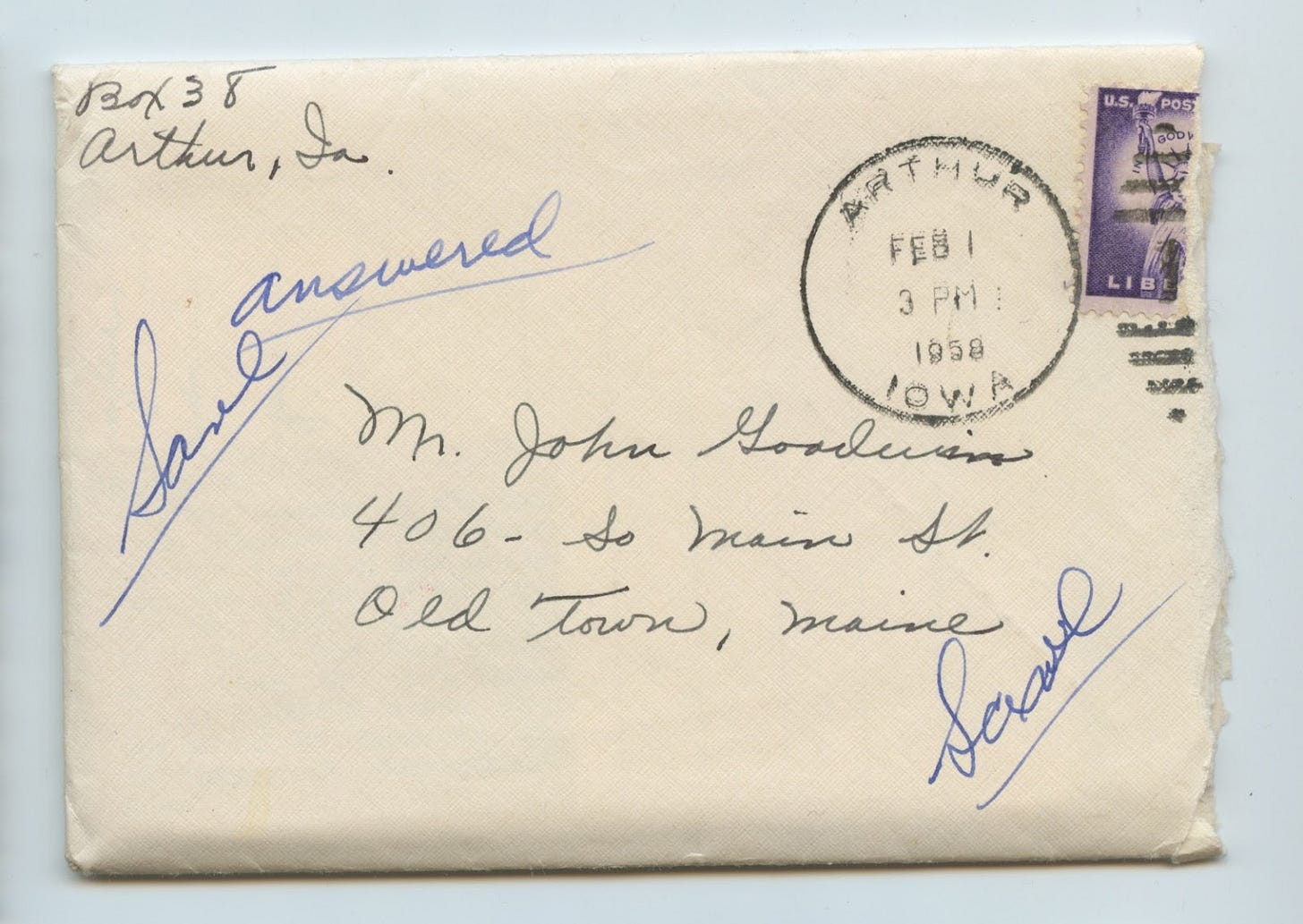

Following the tragic death of Phyllis, Grandpa John sent my Dad to live with his sister in Iowa. It must not have taken long for Grandpa John to deem himself unfit to care for a child alone. Phyllis died on December 11, 1957 and by February 1, 1958 my Dad was living in the tiny town of Arthur, Iowa with his Aunt Leila and Uncle Duane, according to postmarked envelopes that my Dad kept, which I now keep.

In explaining this episode, my Dad would say that Grandpa John wasn’t ready to be a single parent and that he was a man of his time (meaning child-rearing wasn’t considered a man’s responsibility in the 50s). I never questioned this too much until I started reconstructing timelines for this essay, and I realized Grandpa John was 36 when all of this occurred. I had always imagined him as an overwhelmed 25-year-old, but he was actually a grown man. To father a child you can’t be bothered to care for at that age is reprehensible.

Grandpa John didn’t resume custody of my Dad until years later after he had remarried. Elaine was a fellow widow who had lost a child of her own, and I wonder whether Grandpa John chose her out of love or if he just saw a caretaker in her.

This timeline is savage in every way: Phyllis dying two weeks after her 27th birthday, and four weeks after my Dad’s second. The fact that Grandpa John, age 36, arranged to send my Dad halfway across the country in less than eight weeks and didn’t resume custody until years later.

And yet. Despicable as John’s behavior may have been in my eyes, my Dad recalled those years in Iowa fondly, often saying they were among the happiest of his childhood. I believe it. In the letters Leila wrote to John, I can see how tender she and her husband Duane were toward my Dad, raising him as if he were their own. “Friday night Duane took him to the Father & Son banquet and he was a perfect little man.”

I see how Leila tried to subtly coach her brother John on how to be a better parent. “He is very good most of the time,” she wrote. “Now and then he gets crying streaks and torments, but we all do that. We want him normal.”

Dad told me he never once saw Grandpa John cry.

The photos, the timeline, the letters: I’ve come to fear my Dad was little more than an inconvenience for high-flying Grandpa John. But these letters also helped shed some light on my father as a child. I sense a young boy craving connection as he grapples with abandonment.

“He hasn’t broken any dishes since you left,” Leila reported in her first letter.

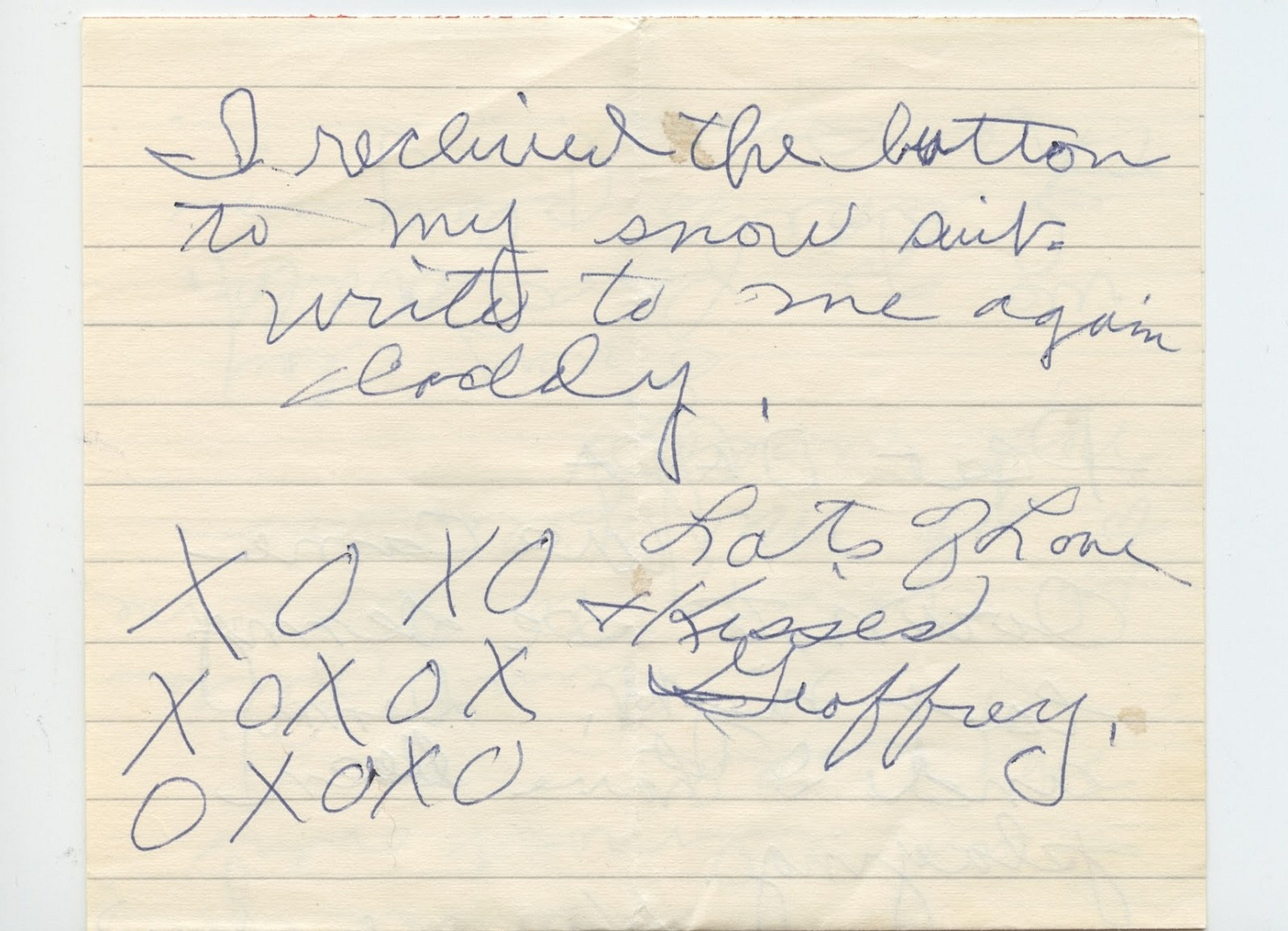

And later on: “Geoffrey really doesn’t like to have me leave him but he is becoming more used to Helen…When we go down town in the car he waves to everyone on the street and when we are walking he says Hi to everyone.”

The need for connection is also evident in letters my father “wrote” (unclear to me how a two-year-old was writing in cursive, perhaps Leila gave her hand to his words).

The passage that moved me to tears was the first paragraph of the first letter. “[Geoffrey] was very pleased to hear your voice last night. His face sure brightened up. I have two pairs of your socks I have been intending to send you. This morning, I put them on the table in the kitchen so I could wrap them today. Geoffrey says, Duane’s socks? I said, No, Da Da socks. Should we put these in a box and mail them to him? He says yah then he took them off the table and played with them most of the morning.”

The image of my newly orphaned Dad playing with his father’s socks, cherishing what scraps he has, is crushing. But that was something my Dad always excelled at. He knew how to make do with very little, how to find joy in the slightest of openings.

I didn’t recognize it initially, but I am essentially mirroring my father’s behavior in this essay, studying photographs in lieu of playing with socks. In both instances, we took what we had of our father and held it dear.

In the last year, I’ve worked steadily to revise, if not completely undo, how I saw my Dad. If Grandpa John framed my Dad as distant, small, and alone, I had framed him as a failure; inept, needy, and lonely. In my eyes, my Dad was a frustrating, tragic figure who was doomed to a life of loneliness and blessedly oblivious to his many shortcomings. But most of that was forgivable, because he was so earnest, so unafraid of expressing his love for you and the world and everyone in it. I knew he never intended any harm.

After he passed, I extended that grace further, casting him in a new, buttery light to overwrite my long-held prejudices. It was liberating to do so. Not only was I shedding a great, haunting weight, but I also felt like I was seeing my father in a fuller light now that I was no longer fixated on his faults. After dislodging these stubborn, calcified feelings of bitterness, it was exhilarating, and a relief, to discover cavities full of affection in their stead.

The project of revising my image of my father began when I sat down to write his eulogy. A lot was riding on this speech for me. I had had so much to say about my Dad for so long, but I seldom expressed any of it. I don’t believe in being honest when being honest means hurting those you love. I would rather be the one to hurt, even though I am a small container for such things and my venom inevitably seeps out in other ways. If this sounds at all benevolent, make no mistake — this is a matter of courage, or a lack thereof I figured I could be as brutally honest as I wanted whenever he died, and I seized on the first opportunity that presented itself: his eulogy.

I had known the first line for a long time: “I’ve tried to write about my Dad a thousand times,” which is another way of saying I’d thought about my Dad dying a thousand times. I wrote the rest of the eulogy from a place of deep shame and even deeper guilt. I felt ashamed of what my Dad had become, the things he did and didn’t do, and felt terribly guilty for focusing squarely on his flaws in our final years together.

The eulogy became confessional. At that charged hour, I did not reach for truth but beauty, and I located that beauty in reconciliation. In that moment, I could not hurt anymore than I was already hurting, but I could be wrong. I could be gloriously, wonderfully wrong. And I would be happily wrong if it meant my Dad was a little less lonely and a little less miserable than I had feared.

Now, I’m reaching for truth. Studying these photographs and reading these letters to reconstruct my Dad’s early childhood has reopened old wounds and anxieties surrounding my father. The whole experience has been unsettling — not just the ghostly apparition and the cruel timelines, and being freshly convinced of my father’s orphanhood — but also because it made me question if the pockets of peace I’ve found following my Dad’s death weren’t a convenient fiction I’ve afforded myself.

I’m convinced now I was right to fear for my Dad’s well-being and for his loneliness, but I’m equally convinced I was wrong to underestimate him. Recounting to Celina what I uncovered about my Dad’s childhood, she said it’s remarkable that my Dad became such a loving person. It is remarkable. It also helped me understand why my Dad didn’t feel the need to strive to succeed in this world. Having overcome what he did, he was perfectly content to have found a family, to love and to be loved.

When you grow up in a household as loving as I did, you can afford to feel betrayed by the world.

Great piece Connor! It must have felt good to get all the poison out.

I'm sorry about what you went through recently, but I can see that you've emerged a better person on the other side--or at least you are in the process of emerging.

This business of reframing the lives and struggles of our parents is not an easy one. I am in the process of doing that myself. I started it as a way of trying to shield my son from the poison that has been passed down to me.

I use music as a springboard for social commentary and personal reflection. I wrote a little piece about the song "Cat's in the Cradle" recently that may resonate with you. It's very much a spiritual sibling to your piece on reframing your father.

https://substack.com/@maninplaid/p-160037008

Thank you for your work and have a great day!

Read this hours ago. Started a response. Read it again later. Just in awe of how you wrote what you wrote. My heart breaks for my friend.