“The people we love deserve to return to the places they left with the things they love intact.” —Hanif Abdurraqib

I realized how lethal loneliness can be after my father nearly died. And he very well might have, if it weren’t for a dog.

In May 2023, a stroke, cloaked in the dark of night, struck my father to the floor, out of the bed he was sleeping in and out of reach from his cell phone resting on the nightstand. He cried out for help, but he was alone, dog-sitting for a friend. With no one around, he army-crawled from the bedroom, through the living room, down the porch, and onto the front lawn where he cried for help again. And again and again. 30 minutes. That’s how long he estimated it took for someone walking by to call an ambulance, though he was confident one of the neighbors must have heard him before then. In his retelling, he always teared up recounting how the dog never left his side—kissing him, nuzzling him, pulling him back from the edge—until help arrived.

The stroke forever changed my Dad’s life. He would never walk again and he now required around-the-clock care. His handwriting, once an elegant cursive, devolved into chicken scratch. He developed something of a lisp and talking for 15 minutes or more was a tiresome effort. Thankfully, his mental faculties remained intact, and he slid in jokes whenever he could.

I first learned of the stroke from my Mom who phoned me late one Sunday night. Normally I’d ignore such a call, but it was unusual for Mom to ring so late. When I called her back, she was walking into the hospital room where Dad was staying. I could hear him in the background and that’s when I knew it was serious. It was him, and it wasn’t. I recognized the pitch of his voice, but not his words. They were shapeless, garbled, the babble of a child.

I booked the first flight home to Nebraska and spent the next month commuting from my Mom’s new house in the suburbs of Lincoln to Omaha’s renowned medical center less than an hour away.

But this essay isn’t about recovery, it's about loss, irrecoverable loss. And it isn’t about loneliness either, even though there’s an epidemic of loneliness quietly dragging America under and my Dad was a whistleblower on the topic, sharing studies reported by The Washington Post. I promise it isn’t about loneliness even though I took a book of essays titled The Loneliness Files from my father’s library after he died.

This is an essay about my father’s kingdom, by which I mean his library, and how I came to destroy it.

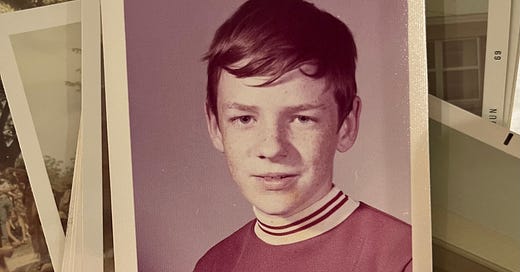

Recalling the act of my father reading reminds me of prayer. He liked to sit with his legs pretzeled, impossibly criss crossed and improbably limber for a man without a shadow of athleticism. He’d sit like this on the floor, neck craned over his book, finger tracing the page line by line as he muttered the words to himself in a hushed whisper. As a snooty smarty pants kid, I thought this childish. Adults don’t read with their finger or talk aloud, kids do. But now it strikes me as beautiful, rapturous even, in its singular devotion. He cut a monastic figure in this light, a model of absolute concentration.

My Dad’s love for books and reading was pure. And while he came to love dogs so deeply late in life, valuing their companionship when he had not known touch in decades, I think books were his truest, most loyal companion.

Books always kept him company. He never left the house without three or four stuffed in his backpack. I’m not talking about slim books, either. My father had an affinity for fatties. He liked meaty biographies of great men, sweeping histories of wartime, and other door stoppers.

Dad never dated after he and Mom split up but he also never slept alone, for there were always books in bed beside him. He suffered from insomnia and whenever sleep evaded him, he reached for a book.

My Dad took a unique approach to reading, one I have never seen replicated. He often read ten books at a time, making glacial progress in each. The assortment was always wide-ranging. History, specifically World War II history (classic dad), and sports were two of his mainstays. But he was a generous reader with an omnivorous appetite.

Forever a student, he continually tackled new fields of knowledge as his appetites evolved. As a young man, he wanted to be a sports journalist. Reporting on high school ball for small town papers in Nebraska and Minnesota, he dreamed of one day writing features for Sports Illustrated.

Later in life, his reading took a more romantic turn toward religion and art, mirroring an introspective turn within himself. In his loneliness, he sought community in church and that faithfully filled his cup for many years. I still regret never going to a service with him. (For the record, we tried going together one Christmas Eve but Dad misremembered the start time.)

In his old age, he thought about death, a lot. It became such a frequent topic of conversation that eventually I told him I’d prefer not to think about him dying every visit home and every other phone call. I think he saw art less as a gateway to the eternal, a means to transcend death, and more so a way to measure the fullness of life.

I promised you a kingdom. Maybe you don’t see it yet, but rest assured I am building it, brick by brick, book by book.

Growing up, Dad would read to us sometimes. I recall one summer choosing a long, 500-page book called Summerland, a Michael Chabon YA novel that had a fantastical large yellow blimp on its cover. I don’t remember what it was about but Wikipedia tells me it centered around children playing baseball to save the world, which makes me second guess whether I chose the book because that is precisely something my Dad would pick up.

We never finished that book. Dad didn’t finish a lot of books, prolific as he was. Those who didn’t know him well, knew him to be bookish. And those who knew him best, ribbed him for not finishing what he started. Members of his book club dubbed him Mr. 30 because he had a penchant for only reading the first 30 pages. But that didn’t deter him from sharing his thoughts. He’d hold court just the same, voicing his opinion as fervently as anyone who finished it while begging them not to spoil the ending.

We visited the library, often at my mother’s insistence. I remember well the exterior breeze blocks of the downtown branch, and the futuristic floating stairs that lead to the second floor. It was there I’d find my father, wandering the aisles of adult nonfiction.

My brother and I had our own library cards, but Dad commandeered them after he racked up too many fines to use his own. Soon enough our cards were also burdened with late fees and the Goodwin clan was altogether banned from the Lincoln public library.

Dad preferred bookstores over libraries anyway. Money was always tight growing up, but books were not an expense to my Dad, they were a God-given right.

My Dad took a collector’s pleasure in owning books, by which I mean he did not need to make use of them to derive satisfaction. He could admire them as objects, though they were so much more than “objects,” which sounds heartless and clinical. As I said, books were companions. But they were also portals, mirrors, frontiers, lighthouses, medicine. What I’m trying to say is that bound between the covers of a book is a slew of possibilities where great repositories of knowledge remain untapped, a private abundance for the taking that, no matter how much you take, will keep on giving. To own such potentiality, such generosity, was a kind of wealth, and a reliable source of comfort.

I love libraries, but I also prefer buying books, in part because it is always painful to return them. This may sound dramatic, but I don’t think it is, especially after you’ve spent so much time alone, quietly communing. It is, in other words, a kind of loss, one that memory cannot reliably recover.

This is doubly true if you, like me, enjoy annotating books. When I first learned some people write in books, I took offense, thinking it disrespectful. But it also made me curious. What were these whispered asides being had in the marginalia? I also saw how such markings could facilitate a more engaged close reading. Still reluctant to stain the page, I deployed sticky notes and soon my book shelves appeared like an unruly peacock. When I did dare to sunder the page, I did so indiscriminately, underscoring line after line, so that everything seemed important. And to be fair, at age 14, everything did feel revelatory.

I have since pared down my annotations and settled into a minimalist approach. Now, I use a single line or brackets to flag a long passage and parentheses to gently caress a striking phrase or sentence as if I were cupping water in my palms. The parentheses impart a hushed consecration, as if I were whispering to my future self: these words once spoke to you, keep them close in your heart of hearts.

I looked for my father’s hand as I sort through the rubble of his kingdom, but I don’t think he ever crossed that threshold, out of respect or what I will never know. The only instance of his note-taking I’ve heard was a story my mother relayed. While reading a biography of Napoleon, my father kept a running tally in a yellow legal pad. After observing my father’s mysterious accounting for several days, my mother finally asked what he was doing. “These are the number of people who died at the hands of Napoleon,” he replied.

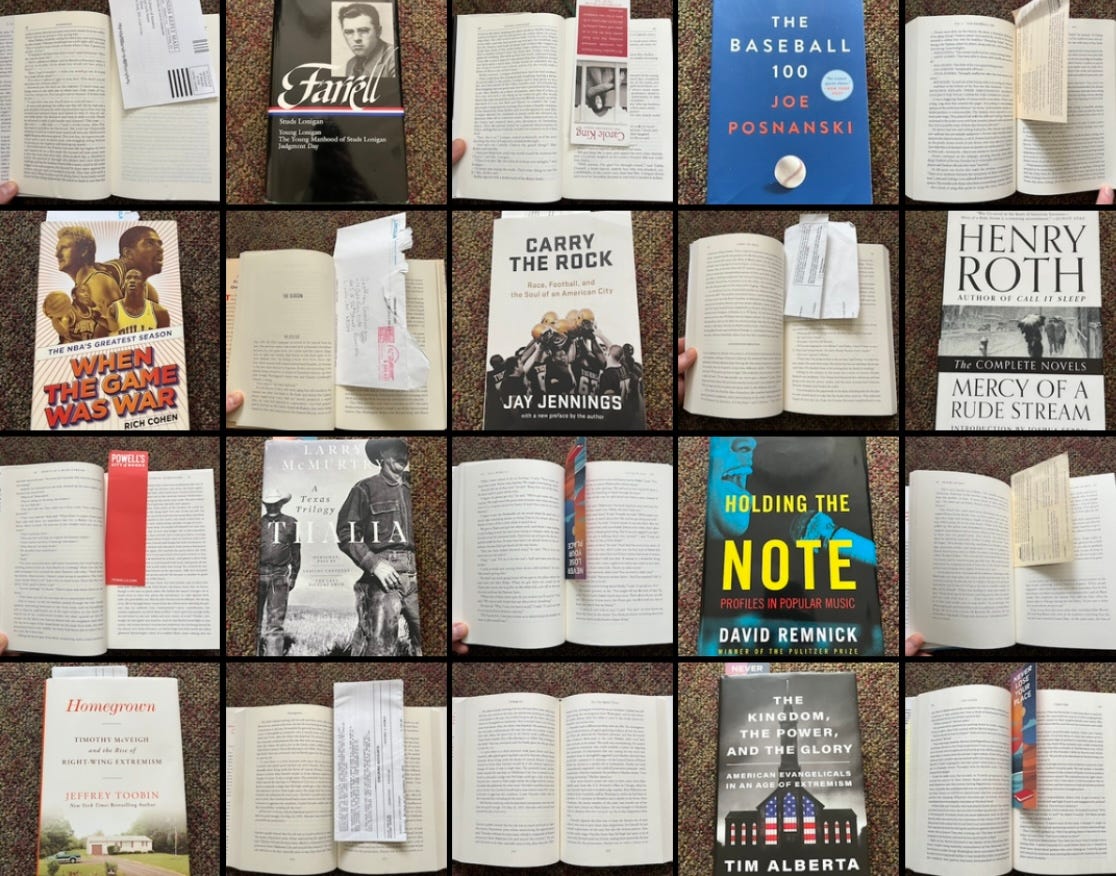

For reasons unknown, my father liked to use mail as bookmarks. Some were ripped open by hand, making the book appear thrashed or gutted. Other mail remained intact like those with the little plastic window, that ironic marker of confidentiality, that crinkled loudly. Others still were hand-written letters in need of reply or letters he authored in need of postage. Sometimes there were multiple papers stuffed in a single book, creating a hydra effect. So when my father tucked into a book, he returned not only to the story, but also to the minute tasks that make up a life.

In my father’s kingdom, language was our homeland, books were our countrymen, and Barnes & Noble was our mecca.

The nation’s largest chain bookstore was our home away from home, our third place, and we spent countless afternoons there in a cloud of possibilities.

We entered the store together and then went our separate ways, with my father first detouring to the magazine section and then the cafe while I beelined toward fiction. In my memory, it was always me who went looking for him. So after an hour, usually two, I’d put down my book and check the history section, then politics, biography, art, music. And when I found him enveloped in possibility, gently floating away, I tugged on his coat and said I was ready to go. He could’ve stayed forever, surrounded by friends he had not yet met.

I spent so much time at Barnes & Noble that I read an entire book from the Artemis Fowl series over the course of a month without purchasing it. I was careful not to open it too wide, lest I crack the spine. And at the end of each visit, I bookmarked my place and returned it to the very back of the pile.

He rarely left without buying a book or two, pulling out a two-inch thick wallet fat with unpaid credit cards spending money that likely would have been put to better use at the Hyvee grocery store next door.

After my parents divorced, Dad landed an apartment nearby, just a 15-minute walk away. Early on, my brother and I would visit him there, but it didn’t take long for the apartment to devolve into unkempt clutter with books piled all around alongside unpacked boxes, dirty laundry, unopened mail, and all the rest. We silently reached a consensus that it was more comfortable going out, so that’s what we did. We went out for lunch, saw movies, browsed bookshops, Barnes & Noble becoming our de facto meeting ground. But we soon discovered no third place, even our mecca Barnes & Noble, can replace a home.

Entering Barnes & Noble now, we no longer went our separate ways. Together, we looked through magazines. Dad bought himself a coffee and something sweet for us, cheesecake or a cookie, while I staked a table where we’d thumb through Sports Illustrated, together. After Dad pried what information he could from two young boys, confused why their father was suddenly questioning them so intensely, we went back to our regularly scheduled programming. But this time, Dad came looking for us, not to say he was ready to go, but to continue asking after us: What caught your eye? Can we recover what was lost between us? Can’t you stay a little longer?

It was Barnes & Noble where I tasted my first frappuccino and stole my first book, a copy of Dharma Bums by Jack Kerouac (classic adolescent). I didn’t understand how the scanners worked so I ripped off the bar code and later charred the edges with a match to mask my deed. Of course this masked nothing, instead calling more attention to the conspicuous absence of a payment method.

Later, when my father’s eyesight became so poor he could no longer drive, he’d call me up and ask if I wanted to go to Barnes & Noble. When he pulled out his wallet, sometimes I’d put my hand on his and say, “My treat.”

Toward the end, I’d pass Barnes & Noble on my way to visit him at the assisted living facility. I did not bring him books then, insisting he had plenty to read. But now I wish I had brought him books by the bushel. It didn’t matter that the room was small, let them lay where they may. That is how he preferred it. There are worse things than a lonely man surrounded by beautiful friends who are mute until you lock eyes with them and promise not to look away.

Can you see it yet? If not, close your eyes and look up in surrender. My father’s kingdom is quiet, but not absolute. Listen closely now. Do you hear his hushed prayer?

My father’s greatest gift to me was sharing his boundless love for reading, and I did my best to return the gift in kind any opportunity I could. No matter the occasion—Christmas, Father’s Day, his birthday—I gave my Dad a book, and took great pleasure in doing so. For Christmas last year, I gifted him a Brooklyn Nets hoodie and beanie, as well as The Library of America’s collection of John Williams’ novels: Stoner, Butcher’s Crossing, and Augustus. I wanted to contribute to his growing collection of LOA titles and had recently read and loved Augustus, an epistolary novel about different factions jockeying for power in a fractured Rome.

If I’m being honest, the John Williams book wasn’t just a gift, it was also an apology. But what is an apology if it is not spoken. So let me say it now: I am sorry, Dad. I am so very sorry that I trashed your library because I didn’t know what else to do. I hope you, reader, whoever you are, can speak those words to whomever deserves to hear them. But if, like me, you cannot speak them without rage tinging their sincerity, then at least you can underline them. Consecrate them now so that a future, more certain self can speak them truly as you look directly into the eyes of your beloved.

I am sorry if I’m being presumptuous. Please forgive me if I am, it’s just that I don’t want to be alone in my regrets. Don’t look away, not yet, lock eyes with me and let me explain so that we might arrive in a place called understanding.

Once my Dad’s condition stabilized, he was discharged from Omaha and sent to an intensive rehab center in Lincoln for a couple weeks of physical therapy. What came after that, no one knew. We knew my Dad was unfit to live independently, but even if we could afford a home nurse, his second-floor apartment was untenable since he couldn’t walk. The task was made all the more challenging by the fact that my Dad had just over $2,000 in his bank account, and health care will bleed you dry in this country, and then some.

Miraculously, a Medicaid bed opened up at an assisted living facility and they were able to admit my Dad. When I say miracle, let me be clear: someone had to die for the bed to become available. Our relief was someone’s permanent loss. Room and board would be completely covered, for a price. The state garnished his social security check leaving him a monthly stipend of just $30.

I was back in New York during all of these developments and flew back to Nebraska toward the end of June to pack up my Dad’s old apartment.

Even though Dad only lived a block away from our childhood home, I never once visited him there. I never asked and he never invited me, and now I could see why.

It looked like an earthquake hit, followed by a tornado. There was so much stuff littered about it was impossible to see the floor. There wasn’t even a clear path to the unmade bed. Coated in a thick film of dust and strewn all around were old clothes, a number of backpacks, tons of baseball cards, photo albums, family heirlooms, pocket schedules, autographed index cards my Dad requested by mail from athletes, and of course, books. So many books. My father’s kingdom was abundant.

The knee-high disarray encompassed two small rooms with some detritus spilling out into the hallway. When we reached the bottom, we found mouse poop, sand, and other sediment from a life unattended.

Taking in the scene, I was transported back many years to Claremont, Oklahoma where my Dad and I worked to clear out my Grandpa John’s second home, which had become a de facto storage unit. Turns out, Grandpa John was also a collector, though some might say hoarder. He was, at least, somewhat organized in his mayhem. I wasn’t even a teenager yet, and I loved everything about that trip. I enjoyed sifting through all the old stuff, heaving it into the giant dumpster in the driveway, and watching movies with Dad back at the motel that Mom would never allow, like Planet of the Apes. My Dad saw things differently. The burdensome and inconvenient task angered him, and standing before my father’s own cluttered apartment, I could understand why. I’m not sure what he kept, but I know he must’ve held on to some things. I do remember he discovered he had a half-sibling from another marriage that his father never told him about.

My Mom referred to all my Dad’s stuff as junk and that’s how we treated it in the mid-summer heat, stuffing nearly everything into heavy duty garbage bags. But I refuse to use that word now. I am being overly precious, I know, but in some ways the stuff you accumulate over a lifetime makes up a life. I can’t verify this in my Dad’s case because I didn’t have enough time to really sit with the materials. I only had five days to sort through everything.

What ensued was an orderly massacre.

I developed a three-tiered system for handling the books while my Mom handled the rest. The first tier was books to keep for my father. His instructions were clear and brief: hold on to The Library of America editions. This aligned with my Dad's fidelity to country and canon. To this, I also added books I gifted him like G-Man by Beverly Gage.

The second tier was books I thought I could sell to a used bookstore to give my Dad some extra spending money. Notable authors, recognizable titles in good condition, and vintage copies that could potentially fetch a good price landed there. Whatever didn’t sell, I’d consider keeping.

The final tier was for donation, and the rest of the books, the vast majority, fell in this category.

The entire enterprise was masochistic. It pained me to work so clinically. I was judging all books by their covers, an elementary affront. But time was of the essence. The end of the month was fast-approaching and, in addition to packing up my Dad’s apartment, I also had to pack for a two-week road trip through the Badlands up to Glacier National Park.

I moved slowly at first, unsure where to begin. It was almost like I suddenly had access to a secret part of my Dad and I wanted to be diligent. I crouched on the floor like he used to when he would read, and combed through his life’s work.

A telling sample: Under my Dad’s old McDonald’s uniform, I found two oracles titled “100 Best Stocks to Buy” dating back to 2005 and 2006. There were also a bounty of anthologies, a format I never cared for much, preferring to play the part of curator myself. There were travel books to Greece and Spain, places he visited once in his youth never to return. I never knew my Dad had such an affinity for sci-fi, but here were scores of palm-sized paperbacks, their trimmings yellowed from age.

I learned other things too including confirmation that my family hails from England, from a small manufacturing town called Hanley, thanks to newspaper clippings my Dad held on to but never shared, probably because he didn't know where they were.

I exercised restraint and only pulled a box-worth of books. Among them were two first edition Vintage publications from the eighties bearing epic covers: Life and Fate by Vasily Grossman and Satanic Verses by Salman Rushdie. I also repossessed a number of New York Review of Books titles to grow my personal collection, adding more gradients to my rainbow shelf. Come to think of it, I only intentionally began collecting titles from NYRB after my father signed me up for a year-long subscription wherein I received a new book every month. Not every title was of interest, but I liked admiring the growing rainbow on my shelf and I liked honoring writers lost in the clamoring halls of history. The titles I pulled were addressed to me from my time working as a literary critic and, unbeknownst to me, had been accepted as tribute by my father’s kingdom. Or perhaps he levied a sin tax against me for not returning home enough.

Looking back, I wish I had been more greedy. I wish I kept the whole lot, even if they sat in a storage unit. That would be better than any grave marker, which my father doesn’t have any way. At least with this arrangement, I could have taken something home with me, learned something new. In this arrangement, returning the borrowed book wouldn’t be painful at all, it would be restorative.

I exercised restraint because I didn’t want to be like my father, didn’t want to mirror his hoarding behaviors. I do not think I will surrender to the same vices; we do not share the same demons. But my aversion to that possible fate, written clearly before me in spilt blood and ink, was so strong it overpowered my sensibilities, making it impossible for me to distinguish vice from virtue. Under this repellent haze, I judged the whole lot to be bad and refused my inheritance.

I was a fool then. Loving books so much they never leave your side; loving books so much you buy hardcovers even when you’re behind on the mortgage; loving books so that you can learn to love the world that has been cruel to you time and again. If any of that is a weakness, then I surrender.

If I’m going to be a fool, then I want to be a fool with you, Dad. Everyone quietly chuckled in disbelief when they learned you died on April Fool’s Day. Even my brother and I laughed, horrified as we were, sitting by your side in the wee hours of the night, holding on to your every breath.

Every breath was a battle that night as your waterlogged lungs shoveled up mud for another sweet gasp of life. It was then and there I finally understood the term “death rattle.” After a long minute of silence and stillness, we bowed our heads into you, thinking you’d drawn your final breath. When all of a sudden your body spasmed terribly, your chest rising toward the gates of heaven as your lungs clawed for oxygen. You scared the shit out of both of us, but we had to tip our hats with a laugh. You got us good.

When my father did draw his final final breath, my brother and I stayed by his side, unwilling to leave because leaving would mean never seeing him again. I held his hand, rubbing the pad of flesh between his thumb and index finger, until his hand went cold, which happened faster than you’d think. Not long after, his color flushed away too.

It is a truly bizarre experience to watch someone die. Feeling my father’s warmth seep away and seeing his color fade to gray made me entertain the idea of a soul, envisioning it as some invisible hearth within. What else could animate life? I still can’t believe how thin the threshold is between living and not.

But this story does not end in ruin. On my father’s deathbed was a book I’d never seen, Barcelona by Robert Hughes. My father, insatiable as he was, began rebuilding his collection almost immediately after we donated his library to Goodwill. A king cannot be denied his kingdom.

When my brother and I flew home in early November to surprise him for his 68th birthday, his room in the assisted living facility had begun to devolve into a familiar clutter. There were opened packages strewn all about the floor, stacks of notepads on a crowded nightstand, inexplicable cans of pineapple, tissues, framed photographs, and a plant or two lined his window sill. But most of all there were books. Beautiful, bountiful books.

At first, I protested his book buying. This was a gross misuse of his meager funds, I reasoned, as the horror of his hoarder apartment lingered fresh in my memory.

But I was also haunted by what I’d done. Despite my father’s instructions to only keep the Library of America editions, he called me in the weeks following to ask after this or that book. Heavy with disappointment, I’d tell him that book was long gone, and we’d both relive the anguish of that mid-summer atrocity.

In that interim, I thought about how devastated I would be if someone took my books away from me. Not only my books, but also my ability to walk, my independence, my pride. So much had been taken from my father. I couldn’t fathom how it weighed on him. Whether it was right or wrong, practical or not, I no longer wanted to deny my father his kingdom. Let him return to his paperback throne.

The book I gave my father for Christmas—the Library of America edition of John Williams’ novels—was a gift and an apology, yes. But it was also a brick.

When the third stroke stole my father’s life, I was so grateful he had a library for me to sort through. I knew what to do this time. I knelt to the ground and slowly thumbed through my father’s new library. I took a series of photos documenting all his bookmarked books, the cover first and then the page marked. My writerly brain sensed some opportunity here, to what end I couldn’t say, but I hoped to glean some insight into my father’s final days. Perhaps these bookmarked pages could offer a snapshot of my father’s psyche?

As I photographed, I skimmed the pages in mild desperation. I wanted these passages, plucked from their proper context and spread across genre and time, to form an archipelago abundant with meaning and ripe for interpretation. But there were no islands to be had, no fruits to be harvested.

I did, however, find something I had been looking for. I was on a sci-fi bender at the time and the next book on my to-read list was New York 2140 by Kim Stanley Robinson and, by some miracle, my father had a copy waiting for me. Thank you, Dad, for that final gift.

Even if my father’s library was never destroyed and had remained perfectly intact, it would be but a pale shadow of him. A king is not his kingdom.

“He liked to sit with his legs pretzeled, impossibly criss cross-crossed and improbably limber for a man without a shadow of athleticism.”

Connor,

Makes me smile to recall that Goodwinian reading posture. And to contemplate his retort defending his athletic prowess.

Just amazing writing. You are in a league of your own.

Dammit Connor, I have a million things to do today, but now my world has stopped. I’ve had to read and reread, laugh, cry, send to Kate, and reminisce. This is a fabulous read. I’m so glad you had a celebration of life for him, so you could witness all the love in the room. I brought home the book “Carry the Rock” mostly because the title spoke to me. I definitely carry your father in my heart. I’m so happy that you’ve come to accept Geoff for the odd, but beautiful man that he was, and write about him with such compassion. More, more, more! ❤️