Headmaster's Field

Race report from Deerfield Academy

We are not a proud race / it’s not a race at all — Carseat Headrest, “Drunk Drivers/Killer Whales”

Men in skin-tight lycra mill about, rear hubs clicking as they steer their bikes over the trampled grass to the six porta potties whose plastic doors swing open and slam shut like a saloon. The mood is light and festive, the day is young and bright, but I am restless, eager for the gun to sound and unleash the stampede. Ahead of me lay 70 miles and 8,000 feet of elevation on backroads through an area of Massachusetts so green and granola it screamed Janet Planet.

It’s 6:10am and glass-blue mist rises cloud-like from the grassy field attached to Deerfield’s Academy manicured campus known as Headmaster’s Field. We camped here overnight, after two tall boys by the river and a cigarette on the bleachers. I woke up in the damp repeating the mantra “basin and range,” lifted from John McPhee’s Annals of the World, with vague memories of a dream about child abduction in an underground Ohio lab where kids were made to cuddle and I was a “cuddle lawyer” working the case. In real life, I am something of a cuddle lawyer, litigating the conditions (temperature, location, time of day) under which I’m okay being touched by Celina, who is something of a cuddle warrior, constantly fighting to advance the rights of cuddlers. My race isn’t scheduled to start until 8:30am.

It’s 8:23am and I’ve been ready to ride since 7am. I didn’t train much for the race, but while surveying the crowd of older men at the registration tent the night prior I started thinking, Maybe I could win this thing. My fellow riders are largely retirees, and though their bronzed arms suggest long hours pedaling under the sun and their carbon bikes are superior to mine, the varicose veins that rivered through their calves suggested I may have an advantage.

It’s 8:28am and I’m thinking back on all the races I’d run and feeling nervous, not as much about how I’d perform because I had no baseline for comparison, but about being reliant on equipment to complete the task at hand. Despite pledging to treat my Salsa better than all my previous bikes, I showed up to my first ever race with loose brakes, a grimy chain, dusty frame, and bar tape so scuffed that one end dangled loose as an errant curl not unlike a Hasidic payo. As nervous as I am for the elevation, I’m more anxious about a technical mishap I can’t troubleshoot, which basically amounts to anything beyond a flat.

It’s 8:35am when I realize there is no gun, other than the one I’d been holding to my head. This isn’t a race at all, but a gentleman’s ramble along well kept roads with aid stations located in towns settled in the 18th century, incorporated in the 19th, abandoned in the 20th, and redeveloped in the 21st.

10 miles in I sort of relax, start composing this in my head.

15 miles in I chide myself for downgrading from the 160K to the 105K weeks earlier.

18 miles in an older gentleman asks, “How do you like the 650bs?” referring to my wheel set. Here it was: the dreaded Shop Talk. All weekend I’d been wary of getting roped into any discussion that risked veering into the domain of Gear, Specs, Repair, or Mechanics. It was a domain of masculinity I preferred to sidestep altogether. “It’s hell getting them on and off,” I said, which he chuckled at and, before the conversation could go any farther, I saluted him with my email-hands, which are soft and clean, and rode off to tackle the first big climb.

30 miles in I’m gasping uphill and thinking nonstop about the lakeside lunch waiting five miles up a gently graded highway frequented by busloads of rafters ready to float down the fossil-dense Connecticut River.

60 miles in I can’t muster the wattage for the final big ascent. Not even Pain will get me up this hill. I look over my shoulder—no one is behind me—and I decide to walk the rest of the climb.

70 miles in I cross the finish line at 18 mph listening to Beastie Boys “Sabotage.”

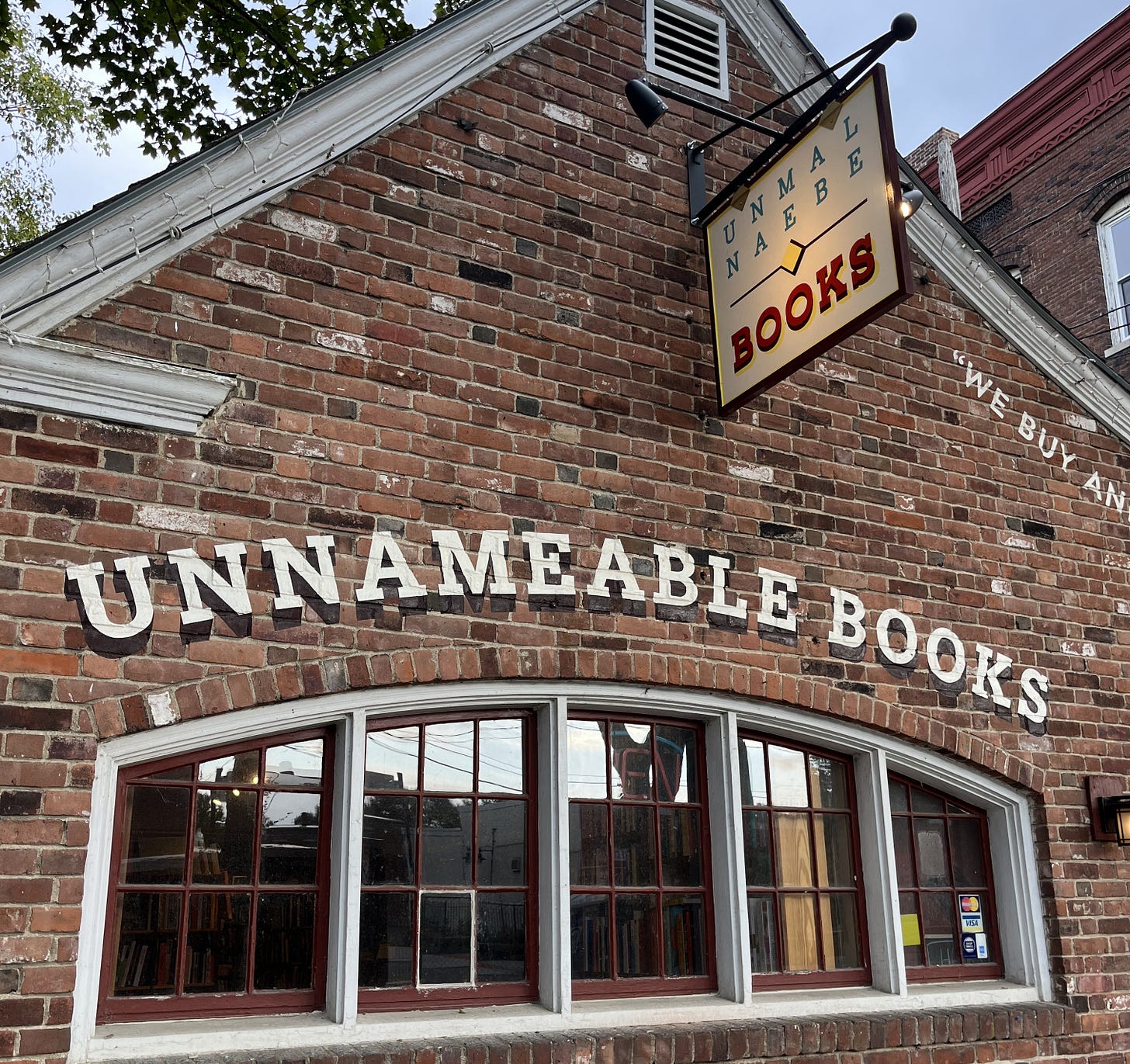

The next day we had breakfast in town at a cute spot with strong coffee. Breakfast was three bite-sized biscuits with rhubarb jam, a chunky tomato toast seeded with everything seasoning, and two nicely textured beany carrot patties. I thumbed through the local paper as we waited for our food. The local library, which was housed in a century-old Carnegie building, was to be rebuilt in an empty lot nearby after a decades-long deliberation among the board. This made front page news, trumping my own efforts back in the city. After breakfast, we cycled along the canal killing time before a previously unknown sister store to Unnameable, my favorite bookshop in Brooklyn, opened.

The canalside path was smooth and flat and darkly paved. Across the controlled waters, in which a family of swans stood atop some unseen platform, was a row of brick buildings with windows blown out or boarded up. A narrow chimney towered several stories high and pedestrian catwalks connected the residential area to the factories of before. We imagined, as we do anytime and anywhere we go upstate, what it would be like to live there. It seemed like a very fun place to explore as a child.

When Unnameable finally opened 15 minutes late and I oriented myself to the different layout, I headed to the used fiction section where I picked up book three of Karl Ove Knaussgaard’s My Struggle series and a copy of Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain. The most learned man I ever met, a Canadian with doctoral degrees in physics, psychology, history, and law who stopped in the remote mountains of Guatemala to brush up on his Spanish before heading off to Peru to take peyote, told me that Magic Mountain was the best book ever written, but I have yet to confirm this for myself. It would have to wait longer still, because the copy in my hand was peculiarly formatted and of poor quality, so I returned it and wandered over to the literary nonfiction section. There, I pulled Bill Buford’s Among the Thugs about soccer hooligans, a handsome vintage copy of Great Plains by Ian Frazier with an illustrated map inside, and Random Family by Adrian Nicole LeBlanc, which NYT ranked 25th in its top 100 books of the century.

There were also two John McPhee books I was deciding between: Uncommon Carriers and The Headmaster. Neither seemed especially interesting at a glance, but McPhee’s talent lied in making just about anything interesting if you only paid close enough attention. He famously wrote an entire book about oranges, which I didn’t care for. I’ve slowly amassed a collection of his white-spined FSG titles over the years (thank you to Matt, who often brings me a McPhee after trips to Massachusetts and has helped build this collection).

Celina encouraged me to get The Headmaster because of the field we slept near, but Uncommon Carriers with its focus on transport interested me more than the biography of a school administrator.

On the drive home I read about Deerfield Academy to better understand its immaculately maintained, regal campus, a good portion of which was undergoing renovations. Founded in 1797 while Samuel Adams was governor of Massachusetts, the boarding school is one of the oldest in the country and today charges up to $75,000 in tuition. By the turn of the 20th century, however, the school was in dire straits and nearing closure. Its financial position was so precarious that no one in their right mind wanted to take the job of school headmaster. Enter 22-year-old Frank Boyden. A gifted fundraiser and savvy marketer, Boyden brought the school back from the brink of financial ruin, padding its endowment and burnishing its reputation such that the “Deerfield Boy” became synonymous with New England conscience and character. When Boyden died in 1972, the New York Times wrote that he was "the best known American headmaster of his times,” having transformed "a dying village institution and made it a notable preparatory school.”

Before Boyden appeared in the Times, he was profiled in The New Yorker by a graduate of Deerfield Academy named John McPhee, who later expanded his article into a book called The Headmaster.

“I told you,” tsked Celina. “Should’ve gotten the book.”

Amazing! Amazing writing and amazing that you did 70 miles w/out training! Thank you for sharing your writing.

I'm always mesmerized by your writing. Your life amongst books is so much like your father's, but I'm doubting he even knew how to ride a bike. Did he? Although we would go skinny dipping after the bar closed and he didn't know how to swim. Good Lord.